Thoughts on the Story of the Absconder, Martin Guerre

After a violent conflict with his father, Martin Guerre, sixteenth-century Gascon peasant of Basque origin, leaves behind his young wife, Bertrande, and infant son.

Eight years later, Martin Guerre returns. The man claiming to be Martin knows everyone in the village. He possesses memories of intimate details. This Martin is a changed man, kind and loving, whereas the younger Martin had been prideful and distant.

But this new Martin Guerre, more focused and self-assured, makes enemies within the family and in the village. Small doubts give way to accusations. The town is divided; Martin’s wife, Bertrande, is herself of divided mind and heart. Martin’s uncle pushes his accusations until the matter is brought to court, where one day another man enters, maimed from the wars. He claims to be the true Martin Guerre.

After some spirited resistance, the man on trial admits to being one Arnaud du Tihl, “Pansette,” a man from the region of Sajas. Du Tihl is hanged before the home of Martin Guerre, who, though imbittered and one-legged, regains his home, family, and property.

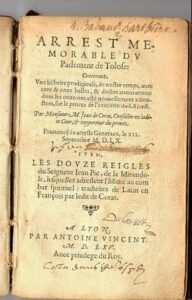

Public-domain image of the title page of Coras’ published account.

The story comes first through an account by the chief jurist, Jean de Coras. Montaigne makes brief reference to the case of Martin Guerre in his essay “On the Lame.” Both men, Montaigne proposes, are justly identified as Martin Guerre. “I remember,” writes Montaigne, “… that he [Coras] seemed to have rendered the imposture of him whom he judged to be guilty, so wonderful and so far exceeding both our knowledge and his own…that I thought it a very bold sentence that condemned him to be hanged.” Montaigne declares his wish for judges who defer in the face of uncertainties, who might command the concerned parties “to appear again after a hundred years” — in Roman times, the time-frame of resolution in missing-persons cases.

To this day, others – novelists, librettists, historians – have re-examined the story of the absconder and the impostor. Alexandre Dumas’ 1840 version of the Martin Guerre story emphasizes the doubled nature of the claimants – perhaps not so far in intention from Montaigne, seeing that we are never exactly the same individual across the years, and might even bleed into one another in strange ways. In Dumas, the two soldiers are taken for twins by the military surgeon who tends their wounds. Dumas draws out the malevolent nature of Arnaud, particularly in the way Arnaud compels Martin to reveal his story by withholding water while Martin lies wounded. Later, when Bertrande begins to doubt, Dumas emphasizes her love and faith. In his reconstruction of the trial, Dumas hints that belief alone makes a man who he is.

In Philip K. Dick’s short story “Human Is” a surly, heartless husband takes an assignment on another planet. His wife has had enough and plans to divorce him when he returns. But the husband who comes back is totally changed: pleasant, loving, playful, caring. She tells a friend, who pursues an investigation, knowing that the husband has recently returned from an alien world, Rexor, whose inhabitants are known body-snatchers. But the wife, called to testify, denies there’s been any change at all. She chooses the compassionate alien over a cruel human.

Janet Lewis’ 1941 novella “The Wife of Martin Guerre” vividly recreates Bertrande’s point of view. Lewis’ Bertrande, as a study in doubt and its heroic possibilities. Her Bertrande is drawn in by the stranger, enough to bear him two children in the years that follow.

The story builds across the recurring, gnawing, terrible doubts that eventually lead her to accuse the stranger as an imposter – in the very midst of what has been a wonderful life with this kinder, gentler version of the younger Martin. Already Lewis’ Bertrande had felt separated by her doubts from everyone and everything. Was she the wife of a somewhat cruel, callow, ambivalent man, or of a vibrant, forceful storyteller of great appetite? Or was she just herself, in a world dominated by men? The village priest had accepted du Tilh as Martin, as did the other members of the Guerre family. When she tells her suspicions to a sister-in-law, the woman asks why Bertrande is so circumspect. “Not for his kindness,” so unlike the boy she had married, “but for the manner of his kindness,” says Lewis’ Bertrande.

Bertrande’s doubt is central – not her belief, and not the trick that du Tilh has played, but the way Bertrande herself seeks a careful understanding between the joys and misfortunes in her life. Re-reading the novella, I see a careful calibration of a woman’s sense of identity between those joys and misfortunes, which are mainly constructed from the choices and errors of men.

Janet Lewis’ version is also a story of faith: Bertrande fears for her soul if she has given herself to the wrong man. Others in the village have their reasons for accepting du Tilh as Martin, or for not accepting him. For Bertrande, it’s everything to do with who she really is herself.

Janet Lewis offers no saving grace to the real Martin. But to the virtual Martin, to Arnaud du Tilh, she offers a form of redemption. After the real Martin Guerre has chastised Bertrande, she staggers in the direction of the false husband, Arnaud. “Madame,” he whispers to his onetime-wife,

you wondered at the change which time and experience had worked in Martin Guerre, who from such sternness as this became the most indulgent of husbands. Can you not marvel now that the rogue, Arnaud du Tilh, for your beauty and grace, became for three long years an honest man?

Bertrande is unmoved. Lewis is not giving us a romance, but a kind of hologram of a woman. Instead of love, Bertrande knows herself “at last free, in her bitter, solitary justice, of both passions and both men.”

*

In writing “Disequilibria: Meditations on Missingness,” I explored many myths, tales, tropes, and types of the Missing Person. Martin Guerre is an example of the Absconder, but also of the Impostor – both, I think, helpful in our understanding of the broader and deeper dynamics of missingness. In months to come, then, I will look further at iterations of the story of Bertrande and Martin Guerre; there’s no omitting Natalie Zemon Davis’ captivating (if controversial) scholarly re-imagining from 1983, “The Return of Martin Guerre,” nor the film she had already advised of the same name. Also, as I keep re-reading, discovering new texts, and meditating on my tropes of missingness, I want to connect this antique tale to other versions of the Absconder: those we suspect of having left willingly, or partly-willingly, whose lives might have continued along different tracks, in different worlds parallel to ours.

This work, to some extend, feels to me like the slow construction of a tarot deck in my mind: a system toward prognostication.

0 Comments