Thoughts on Jessica McDiarmid’s Highway of Tears

Indigenous women in North America disappear at ten times the rate of the general population. Cases tend to occur in Canada along Highway 16 in British Columbia, in the Pacific Northwest, and in the Dakotas, but the crisis is ongoing everywhere.

The causes are various, but include a longstanding attitude of neglect on the part of whites and of white-dominated institutions in national, regional, and local governments, including law enforcement; and lack of agency in most areas of individual and communal life — such as limits, on reservations in the US, of true law-enforcement authority over non-natives who commit crimes on native-owned lands.

Drugs, alcohol, domestic abuse, and sex trafficking are key influences on the high rates of violence and disappearance, but probably nothing exerts a darker, more powerful influence than the historical and ongoing neglect of Native peoples — the centuries-long project of diminishment, theft, appropriation toward extinction that has nonetheless been resisted in its intended absoluteness through the courage of individuals — women and men alone and in concert, defining and redefining community, in part by redefining stories told about the past.

Missingness is a potential condition of the individual: someone goes missing, is missed, is sought for or not sought for. But missingness is also a cultural frame: before humans identified as individuals, we were persons in families, clans, tribes, societies, nations.

Personhood, for me, is the delicate, lively space between the single self and the nurturing/threatening world beyond the skin, the voice, the circumambience we create singly as we walk through the world. Personhood existed before we were individuals with rights; it exists as well beyond the human, defining anyone with consciousness or a will to live.

So, missingness, I am starting to believe, is an evolutionary concept: it matters more for individuals than for persons. Persons are not missed so much as we are remembered, honored, reviled, forgotten, met in dreams or visions, memorialized in story or stone. It is the individual, the person with rights, who goes missing; we each have our roles, our rights/responsibilities, and we’re missed to the extent that we are removed from our familial and social interactions.

I listened to an Indigenous man at the AWP conference in Seattle last week. Here I will make him anonymous, but the man was past seventy, tall, softspoken, though clear-eyed and direct. He told me he was writing about his experience as a boarding-school student — as a child taken away from his parents and forced into one of the “Indian schools” that were common throughout much of the last century. His parents, he said, weren’t told of his whereabouts, and were not given agency over their son. Years later, when these schools were gradually closing, he said that the other students and staff simply started disappearing. No one told the remaining students why others were gone, or to where they had been taken. Eventually, he, too, was taken away, back home — but without acknowledgment of the fact of his abduction or the rightness of his return.

It strikes me that such an experience is a denial of both someone’s individuality and their personhood at the same time. It’s one of the further layers of missingness, missing-missingness, in which it is denied that a person can even be considered missing — that anyone would want to search and find the person.

Acts of terror often exhibit that type and degree of maleficence: to harm, to cause suffering, with intimation that the experience, terrible as it is, could be worse — will be worse — in part, from not being acknowledged at all.

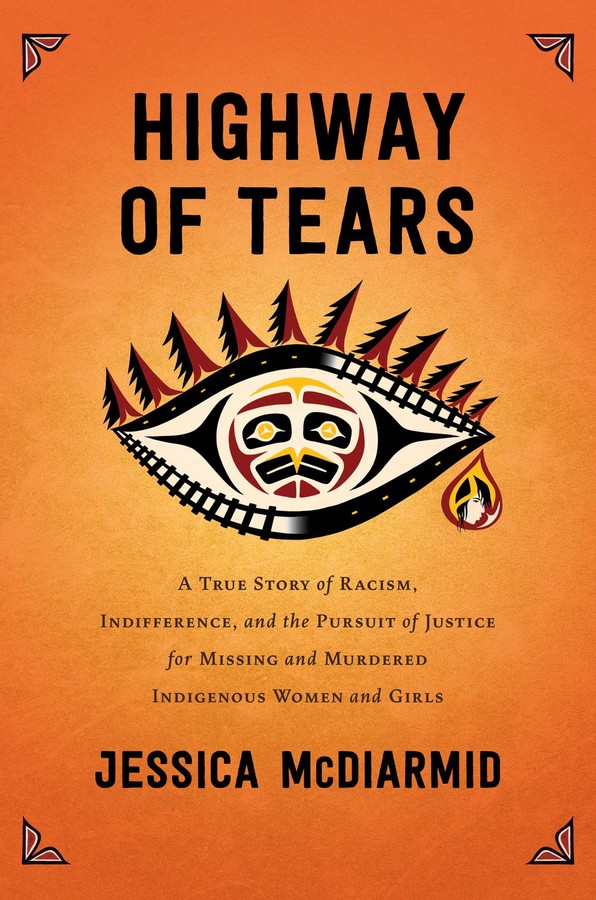

Jessica McDiarmid’s Highway of Tears is an account of the scores of missing Indigenous girls and women whose cases were generally ignored over the past few decades, but whose collective cause has been championed, largely by native families and women in Canada, though with a slow, eventual increase of attention from government and law enforcement.

Jessica McDiarmid’s Highway of Tears

McDiarmid focuses with great care on the identities of the missing women and girls: who they were, what they looked like, how they struggled, what they loved, who loved them, misses them, and is searching for them. The author also provides historical and statistical context, in a mainly-journalistic account that doesn’t often reach for what I think of as the mythic or cosmic dimensions of the experience — which is fine; the book’s purpose is to document, frame within greater discourse, acknowledge and honor the actions and virtues of the people, mainly women, who have made the crisis a matter of general urgency — to make the missing women missing, as much as to find them one by one.

Deborah Halber, in her The Skeleton Crew: How Amateur Sleuths Are Solving America’s Coldest Cases (which I will discuss in more detail in a later post), creates a compelling, if small, image in one of the accounts she gives of a forensic specialist researching an unidentified homicide victim. Agencies across the land use different protocols, tools, methods; there is (in the US, anyway) no central system for working with unidentified remains (though NamUs is a large step in the right direction). One investigator chooses particular-colored Rubbermaid bins for storing the remains she’s working on; one unidentified woman is given a purple bin — a gesture toward her personhood, beyond protocol, but toward some recognition of who the bones belonged to — lacking name or narrative, but anchored by the seemingly frivolous choice of color.

McDiarmid’s clear prose also provides color and form for the girls and women she’s seeking:

Delphine, about three years older than Kristal, was fiercely protective of her younger friend. She made sure Kristal went to school and was headed home by curfew. She steered Kristal away from situations where, Kristal came to suspect years later, people were using hard drugs. During the daytime, while Kristal was cooped up in school, Delphine wrote her long letters. She copied out the lyrics of her favorite song, Tom Petty’s “Apartment Song,” for her friend. She wanted to get her own place when she turned sixteen, a spot in the world that she could call her own.

This is seeming-simple: in its directness, the prose evokes the personhood and the individuality — the gestures, choices, desires, fears, hourly and daily living that, combined, represent who and what is lost. More than the single person, it’s the relationships, the might-have-beens, the alternate lives, the promises held within the fullness of a life.

Some time ago, I read Adam Phillips’ Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life along with Andrew H. Miller’s On Not Being Someone Else: Tales of Our Unled Lives. These works have circled back in my social-media streams, as well as in real-life conversations. Revisiting my reading notes, I find that the general idea of the alternative life, the possibility of lives within a single life, is essential to my thinking on personhood and individuality — and to the limits of individuality in our understanding of who and what we are as living beings. (More on that in a later post, though.)

Still, what strikes me about the objective-yet-compassionate prose of MacDiarmid is that she uses her skill and training as a journalist and writer to construct a vision, despite the submergence of symbol and myth (as I read the book, anyway); that the persistent, steady gaze itself composes a vision of life that is balanced between those lost women and girls, each one accounted for as carefully as possible, and the broader community and world from which they’ve gone missing.

Having read the book, you, too, miss them; their disappearance frames your world, perhaps not with the same urgency, distress, or outright trauma, but with some sense of the dread that curves over the path that lies ahead for everyone.

Highway 16 in British Columbia is representative to me of the vastness, but also the intimate enfoldedness, of the world — of the ways wilderness is without and within. Practically speaking, a key element of its danger is that many people traveling its length have little choice but to hitchhike. They lack their own vehicles — a core part of individualism in our era — and the system does not provide practical public transportation for daily comings and goings. Not too far along in a journey along its stretches, the traveler is swallowed by true wilderness and human aloneness.

It’s an emblem of the danger of the near and the far — that we succumb, sometimes, not only to the greatness of the world, but to the unrelenting nearness, nowness, and immediacy of our lives. One evil man crossing your path in a wilderness is more terrible than the demons we meet elsewhere; it — he, usually — has the power to embody all the inhumanity of that wilderness before the traveler’s small presence.

I’ll return to MacDiarmid, and to MMIW accounts and works, in later posts. Coming soon: Acts of Imagination beyond art in the scholarship/activism of Annita Lucchesi, cartographer —

Meanwhile, look for Disequilibria — it’s been released into the publishing wilds!

0 Comments